© 2023-2024 Oriental Institute, The Czech Academy of Sciences, Kevin L. Schwartz, and Ameem Lutfi

One

of

the

legacies

of

September

11th

was

the

imperative

to

develop

locally

stricter

counterterrorism

measures,

even

in

countries

historically

not

known

for

attacks,

such

as

those

in

Latin

America.

For

example,

Brazil

approved

Law

No.

13,260

in

March

2016,

known

as

the

Brazilian

Antiterrorism

Law,

which

criminalizes

terrorism

and

its

financing.

What

are the origins, logics, and instrumentalization of this law and why should it be considered one of the lasting legacies of the Global War on Terror (GWOT) in Brazil?

After

the

attacks

on

9/11,

the

U.S.

government

structured

the

Global

War

on

Terror

based

on

three

pillars:

military

operations

abroad,

measures

to

protect

national

territory,

and

global

actions

involving

diplomatic,

intelligence,

surveillance,

and

legal

efforts

against

terrorism.

This

logic

prompted

countries

around

the

world

to

adopt

stricter

counterterrorism

measures

and

encourage

the development of their own antiterrorism legislation. In Latin America, the incorporation of antiterrorism laws became a defining feature of efforts to enhance domestic security.

The

urgent

idea

of

combating

terrorism

was

accompanied

by

the

imperative

to

expand

regulatory

frameworks,

increase

budget

allocations,

and

bolster

the

power

and

authority

of

local

institutions.

A

notable

demonstration

of

this

endeavor

was

the

organization

of

the

“Illicit

Financial

Crimes’’

conference

in

October

2009,

held

in

Rio

de

Janeiro,

a

joint

initiative

led

by

the

U.S.

Department

of

State’s

Bureau

of

Counterterrorism

in

partnership

with

the

Brazilian

government.

According

to

WikiLeaks

,

the

event

gathered

state

and

federal

judges,

thirty

prosecutors,

and

over

fifty

federal

police

agents,

along

with

representatives

from

various

Latin

American

countries

(Mexico,

Costa

Rica,

Panama,

Argentina,

Uruguay,

and

Paraguay).

It

served

as

a

bilateral

training project, wherein Brazilian law enforcement and justice agencies received training from their U.S. counterparts.

Promoting

antiterrorism

laws

in

Latin

America

may

seem

contradictory

or

even

unnecessary

at

first

glance,

since

countries

like

Brazil

have

been

historically

untouched

by

terrorist

groups.

However,

the

ability

of

the

United

States

to

extend

global

counterterrorism

efforts

in

allied

countries

in

Latin

America

has

historical

precedents.

Brazil,

for

example,

has

a

history

of

replicating

security policies initially developed by the United States, as seen with the adoption of the

Zero Tolerance Policy

,

the Detecta Security System

, and t

he “war on drugs” policies

.

In

Brazilian

legislation,

the

term

“terrorism”

first

appeared

in

the

1983

National

Security

Law

(Law

7,170)

,

a

remnant

of

the

military

dictatorship

that

criminalized

acts

(such

as

political

dissent

or

affiliation

with

clandestine

or

subversive

political

organizations)

as

terrorism.

Besides

representing

an

imprecise

classification

of

the

term

“terrorism,”

it

was

a

clear

violation

of

the

principle

of

legality and specificity, or the

constitutional exhaustive principle

.

The

replacement

of

the

National

Security

Law

only

occurred

in

2016,

during

Dilma

Rousseff's

government,

coinciding

with

Rio

de

Janeiro’s

hosting

of

the

Summer

Olympic

Games

.

Given

the

global

significance

of

the

event,

there

were

concerns

about

the

potential

targeting

of

the

city

or

participating

delegations,

reminiscent

of

the

tragic

1972

Munich

Olympics

attack.

Furthermore,

this

period

witnessed

a

surge

in

terrorist

attacks

worldwide,

with

over

16,900

attacks

in

2014

and

14,900

in

2015,

as

documented

by

the

Global

Terrorism

Database

.

Under

these

circumstances,

the

Brazilian

government

faced

considerable

pressure

from

other

countries

and

international

entities

to

pass

specific

legislation

against

terrorism,

lest

delegations

opt

to

boycott

the

event.

Consequently, the approval of the Antiterrorism Law in 2016 was expedited and received widespread support in Congress.

However,

the

Rio

Olympic

Games

is

not

the

sole

reason

why

the

Antiterrorism

Law

was

swiftly

approved.

Instead,

the

proposal

presented

to

the

Brazilian

Congress

was

championed

by

then-

Minister

of

Justice,

José

Eduardo

Cardoso,

and

Minister

of

Finance,

Joaquim

Levy.

This

leadership

pointed

out

that

Brazil

had

been

facing

continuous

international

pressure,

particularly

from

the

FATF (Financial Action Task Force), an intergovernmental body dedicated to combating financial crimes, including money laundering and terrorist financing. This pressure played a significant role

in expediting the passage of the law.

The

urgency

to

approve

new

national

legislation

to

criminalize

terrorism

and

its

financing

in

Brazil

was

highlighted

in

the

FATF

Mutual

Evaluation

Report

released

in

June

2010

.

The

report

emphasized

the

need

for

such

legislation,

signaling

the

importance

of

complying

with

international

standards

to

prevent

possible

sanctions

or

blacklisting.

The

Ministry

of

Finance’s

efforts

to

pass

the

Antiterrorism

Law

were

aimed

at

aligning

Brazil

with

global

norms

and

avoiding

potential

consequences,

such

as

heightened

scrutiny

on

financial

transactions

by

international

institutions. Failure to comply could have imposed costs and limitations on the country’s economy.

At

the

same

time,

in

the

early

2010s

Brazil

was

facing

an

economic

crisis

and

eager

to

demonstrate

itself

as

a

secure

destination

for

foreign

investments.

From

the

perspective

of

policymakers,

Brazil’s

adoption

of

an

Antiterrorism

Law

could

be

explained

by

the

need

to

ensure

public

and

athlete

safety

during

the

Olympic

Games

,

but

it

is

also

related

to

the

logic

of

seeking

improvements

for

the

country’s

weakened

economic

environment.

This

intriguing

approval

process

suggests

that

combating

terrorism

in

Brazil

held

not

only

law

enforcement

significance,

but

also

carried

essential

economic

implications.

The

law’s

adoption

signified

Brazil’s

commitment

to

international

standards

and

demonstrated

a

willingness

to

address

global

concerns,

which

bolstered

its

image

as

a

safe

and

reliable

place

to

conduct

business

and

attract

foreign

investments.

Thus,

the

legitimacy

of

Brazil’s

antiterrorism

efforts

extends

beyond

mere

security

considerations and is intertwined with a significant economic rationale.

The

adoption

of

the

Antiterrorism

Law

in

Brazil

divided

opinions.

Some

argued

it

was

an

attempt

by

the

legal

system

to

maintain

a

clearer

definition

of

terrorism.

Moreover,

the

possibility

of

terrorist

attacks

occurring

on

Brazilian

soil

was

considered

based

on

the

following

factors:

(a)

the

diversity

and

reach

inherent

to

terrorist

groups

and

networks

and

their

various

motivations;

(b)

a

lone

wolf

act,

possible

at

any

location;

(c)

the

local

presence

of

foreign

institutions

that

could

be

targeted;

(d)

the

assumption

that

terrorists

are

not

always

located

in

the

same

places

that

are

frequently

affected

by

them;

and

(e)

Brazil’s

expanding

role

in

the

global

international

order.

In

addition,

the

adoption

of

mechanisms

proposed

by

the

counterterrorism

international

regime

reinforced Brazil’s efforts in fighting transnational organized crime, which has always been a priority in the national agenda.

However,

the

Brazilian

Antiterrorism

Law

has

faced

several

critics.

Some

argue

that

Brazil

does

not

face

major

terrorism

threats

that

would

justify

such

legislation.

Further

criticism

stems

from

the

lack

of

clarity

in

defining

what

constitutes

a

terrorist

act

within

Brazil.

When

the

law

reached

the

presidency,

it

was

sanctioned

with

eight

vetoes

referring

to

provisions

such

as

classifying

vandalism

and

sabotage

of

transport,

property,

or

computer

systems

as

terrorism.

According

to

the

Executive,

the

definitions

were

“excessively

broad

and

imprecise.”

However,

the

vetoed

qualifications

do

not

preclude

the

possibility

of

prosecuting

certain

acts

under

the

law.

Thus,

the

final

text

retained

the

broad

and

vague

nature

that

could

allow

instrumentalization

against

specific

social

groups.

While

the

amendments

introduced

some

restrictions,

the

law

remains

flexible

enough

to

potentially

target

political

opponents

or

regime

critics

rather

than

bonafide

terrorism.

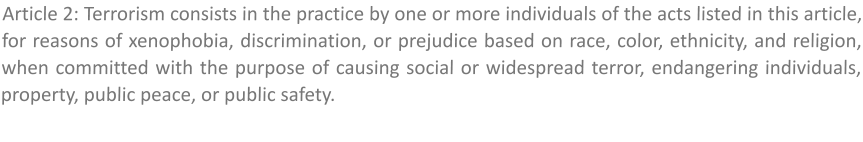

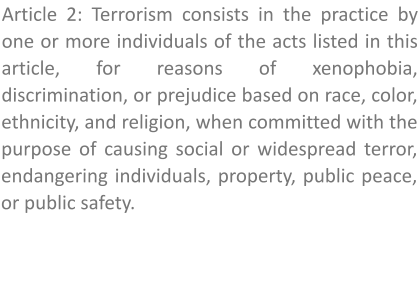

According to Law No. 13,260/2016

:

Thus,

the

final

text

of

the

Brazilian

Antiterrorism

Law

is

so

vague

and

broad

that

legitimate

social

movements

advocating

for

human

rights

and

social

causes,

such

as

indigenous,

quilombola

,

environmental,

and

labor

movements

could

be

accused

of

terrorism

.

Examples

include

the

Landless

Movement

(

Movimento

Sem

Terra

-

MST

),

the

Homeless

Workers’

Movement

(

Movimento

dos

Trabalhadores

Sem

Teto

-

MTST

),

or

even

more

diffuse

social

groups

that

have

aggressively

protested

against

the

state,

as

was

the

case

of

the

Black

Blocs

in

June

2013

.

The

difficulty

in

characterizing

an

attack

as

terrorism

leads

us

to

reflect

on

the

convenience

of

adopting

a

law

that

has

various

ambiguities

and

loopholes,

as

these

social

movements

could

be

delegitimized

and

criminalized simply for being critical of certain governments or specific policies.

In

the

final

analysis,

the

2016

Brazilian

Antiterrorism

Law

is

primarily

a

result

of

international

pressure

coming

from

a

historically

influential

partner:

the

United

States.

Similarly,

the

process

of

approving

the

law

can

be

seen

as

part

of

a

project

for

Brazil’s

international

integration,

aiming

to

strengthen

economic

ties

with

developed

countries

and

align

the

country

with

global

norms

of

good governance. Ultimately, it could also be a strategically convenient instrument for the criminalization of social practices typical of civil resistance groups in Brazilian society.

If you are interested in contributing an article for

the project, please send a short summary of the

proposed topic (no more than 200 words) and brief

bio to submissions@911legacies.com. For all

other matters, please contact

inquiry@911legacies.com.

CONTACT

One

of

the

legacies

of

September

11th

was

the

imperative

to

develop

locally

stricter

counterterrorism

measures,

even

in

countries

historically

not

known

for

attacks,

such

as

those

in

Latin

America.

For

example,

Brazil

approved

Law

No.

13,260

in

March

2016,

known

as

the

Brazilian

Antiterrorism

Law,

which

criminalizes

terrorism

and

its

financing.

What

are

the

origins,

logics,

and

instrumentalization

of

this

law

and

why

should

it

be

considered

one

of

the

lasting

legacies

of

the

Global

War

on

Terror

(GWOT)

in

Brazil?

After

the

attacks

on

9/11,

the

U.S.

government

structured

the

Global

War

on

Terror

based

on

three

pillars:

military

operations

abroad,

measures

to

protect

national

territory,

and

global

actions

involving

diplomatic,

intelligence,

surveillance,

and

legal

efforts

against

terrorism.

This

logic

prompted

countries

around

the

world

to

adopt

stricter

counterterrorism

measures

and

encourage

the

development

of

their

own

antiterrorism

legislation.

In

Latin

America,

the

incorporation

of

antiterrorism

laws

became

a

defining

feature

of

efforts

to

enhance

domestic

security.

The

urgent

idea

of

combating

terrorism

was

accompanied

by

the

imperative

to

expand

regulatory

frameworks,

increase

budget

allocations,

and

bolster

the

power

and

authority

of

local

institutions.

A

notable

demonstration

of

this

endeavor

was

the

organization

of

the

“Illicit

Financial

Crimes’’

conference

in

October

2009,

held

in

Rio

de

Janeiro,

a

joint

initiative

led

by

the

U.S.

Department

of

State’s

Bureau

of

Counterterrorism

in

partnership

with

the

Brazilian

government.

According

to

WikiLeaks

,

the

event

gathered

state

and

federal

judges,

thirty

prosecutors,

and

over

fifty

federal

police

agents,

along

with

representatives

from

various

Latin

American

countries

(Mexico,

Costa

Rica,

Panama,

Argentina,

Uruguay,

and

Paraguay).

It

served

as

a

bilateral

training

project,

wherein

Brazilian

law

enforcement

and

justice

agencies

received training from their U.S. counterparts.

Promoting

antiterrorism

laws

in

Latin

America

may

seem

contradictory

or

even

unnecessary

at

first

glance,

since

countries

like

Brazil

have

been

historically

untouched

by

terrorist

groups.

However,

the

ability

of

the

United

States

to

extend

global

counterterrorism

efforts

in

allied

countries

in

Latin

America

has

historical

precedents.

Brazil,

for

example,

has

a

history

of

replicating

security

policies

initially

developed

by

the

United

States,

as

seen

with

the

adoption

of

the

Zero

Tolerance

Policy

,

the

Detecta

Security

System

, and t

he “war on drugs” policies

.

In

Brazilian

legislation,

the

term

“terrorism”

first

appeared

in

the

1983

National

Security

Law

(Law

7,170)

,

a

remnant

of

the

military

dictatorship

that

criminalized

acts

(such

as

political

dissent

or

affiliation

with

clandestine

or

subversive

political

organizations)

as

terrorism.

Besides

representing

an

imprecise

classification

of

the

term

“terrorism,”

it

was

a

clear

violation

of

the

principle

of

legality

and

specificity,

or

the

constitutional exhaustive principle

.

The

replacement

of

the

National

Security

Law

only

occurred

in

2016,

during

Dilma

Rousseff's

government,

coinciding

with

Rio

de

Janeiro’s

hosting

of

the

Summer

Olympic

Games

.

Given

the

global

significance

of

the

event,

there

were

concerns

about

the

potential

targeting

of

the

city

or

participating

delegations,

reminiscent

of

the

tragic

1972

Munich

Olympics

attack.

Furthermore,

this

period

witnessed

a

surge

in

terrorist

attacks

worldwide,

with

over

16,900

attacks

in

2014

and

14,900

in

2015,

as

documented

by

the

Global

Terrorism

Database

.

Under

these

circumstances,

the

Brazilian

government

faced

considerable

pressure

from

other

countries

and

international

entities

to

pass

specific

legislation

against

terrorism,

lest

delegations

opt

to

boycott

the

event.

Consequently,

the

approval

of

the

Antiterrorism

Law

in

2016

was

expedited

and

received

widespread support in Congress.

However,

the

Rio

Olympic

Games

is

not

the

sole

reason

why

the

Antiterrorism

Law

was

swiftly

approved.

Instead,

the

proposal

presented

to

the

Brazilian

Congress

was

championed

by

then-

Minister

of

Justice,

José

Eduardo

Cardoso,

and

Minister

of

Finance,

Joaquim

Levy.

This

leadership

pointed

out

that

Brazil

had

been

facing

continuous

international

pressure,

particularly

from

the

FATF

(Financial

Action

Task

Force),

an

intergovernmental

body

dedicated

to

combating

financial

crimes,

including

money

laundering

and

terrorist

financing.

This

pressure

played

a

significant

role

in

expediting

the

passage of the law.

The

urgency

to

approve

new

national

legislation

to

criminalize

terrorism

and

its

financing

in

Brazil

was

highlighted

in

the

FATF

Mutual

Evaluation

Report

released

in

June

2010

.

The

report

emphasized

the

need

for

such

legislation,

signaling

the

importance

of

complying

with

international

standards

to

prevent

possible

sanctions

or

blacklisting.

The

Ministry

of

Finance’s

efforts

to

pass

the

Antiterrorism

Law

were

aimed

at

aligning

Brazil

with

global

norms

and

avoiding

potential

consequences,

such

as

heightened

scrutiny

on

financial

transactions

by

international

institutions.

Failure

to

comply

could

have

imposed

costs

and

limitations

on

the

country’s economy.

At

the

same

time,

in

the

early

2010s

Brazil

was

facing

an

economic

crisis

and

eager

to

demonstrate

itself

as

a

secure

destination

for

foreign

investments.

From

the

perspective

of

policymakers,

Brazil’s

adoption

of

an

Antiterrorism

Law

could

be

explained

by

the

need

to

ensure

public

and

athlete

safety

during

the

Olympic

Games

,

but

it

is

also

related

to

the

logic

of

seeking

improvements

for

the

country’s

weakened

economic

environment.

This

intriguing

approval

process

suggests

that

combating

terrorism

in

Brazil

held

not

only

law

enforcement

significance,

but

also

carried

essential

economic

implications.

The

law’s

adoption

signified

Brazil’s

commitment

to

international

standards

and

demonstrated

a

willingness

to

address

global

concerns,

which

bolstered

its

image

as

a

safe

and

reliable

place

to

conduct

business

and

attract

foreign

investments.

Thus,

the

legitimacy

of

Brazil’s

antiterrorism

efforts

extends

beyond

mere

security

considerations

and

is

intertwined

with

a

significant economic rationale.

The

adoption

of

the

Antiterrorism

Law

in

Brazil

divided

opinions.

Some

argued

it

was

an

attempt

by

the

legal

system

to

maintain

a

clearer

definition

of

terrorism.

Moreover,

the

possibility

of

terrorist

attacks

occurring

on

Brazilian

soil

was

considered

based

on

the

following

factors:

(a)

the

diversity

and

reach

inherent

to

terrorist

groups

and

networks

and

their

various

motivations;

(b)

a

lone

wolf

act,

possible

at

any

location;

(c)

the

local

presence

of

foreign

institutions

that

could

be

targeted;

(d)

the

assumption

that

terrorists

are

not

always

located

in

the

same

places

that

are

frequently

affected

by

them;

and

(e)

Brazil’s

expanding

role

in

the

global

international

order.

In

addition,

the

adoption

of

mechanisms

proposed

by

the

counterterrorism

international

regime

reinforced

Brazil’s

efforts

in

fighting

transnational

organized

crime,

which

has

always

been a priority in the national agenda.

However,

the

Brazilian

Antiterrorism

Law

has

faced

several

critics.

Some

argue

that

Brazil

does

not

face

major

terrorism

threats

that

would

justify

such

legislation.

Further

criticism

stems

from

the

lack

of

clarity

in

defining

what

constitutes

a

terrorist

act

within

Brazil.

When

the

law

reached

the

presidency,

it

was

sanctioned

with

eight

vetoes

referring

to

provisions

such

as

classifying

vandalism

and

sabotage

of

transport,

property,

or

computer

systems

as

terrorism.

According

to

the

Executive,

the

definitions

were

“excessively

broad

and

imprecise.”

However,

the

vetoed

qualifications

do

not

preclude

the

possibility

of

prosecuting

certain

acts

under

the

law.

Thus,

the

final

text

retained

the

broad

and

vague

nature

that

could

allow

instrumentalization

against

specific

social

groups.

While

the

amendments

introduced

some

restrictions,

the

law

remains

flexible

enough

to

potentially

target

political

opponents

or

regime

critics

rather

than

bonafide

terrorism.

According to Law No. 13,260/2016

:

Thus,

the

final

text

of

the

Brazilian

Antiterrorism

Law

is

so

vague

and

broad

that

legitimate

social

movements

advocating

for

human

rights

and

social

causes,

such

as

indigenous,

quilombola

,

environmental,

and

labor

movements

could

be

accused

of

terrorism

.

Examples

include

the

Landless

Movement

(

Movimento

Sem

Terra

-

MST

),

the

Homeless

Workers’

Movement

(

Movimento

dos

Trabalhadores

Sem

Teto

-

MTST

),

or

even

more

diffuse

social

groups

that

have

aggressively

protested

against

the

state,

as

was

the

case

of

the

Black

Blocs

in

June

2013

.

The

difficulty

in

characterizing

an

attack

as

terrorism

leads

us

to

reflect

on

the

convenience

of

adopting

a

law

that

has

various

ambiguities

and

loopholes,

as

these

social

movements

could

be

delegitimized

and

criminalized

simply

for

being

critical

of

certain

governments

or

specific

policies.

In

the

final

analysis,

the

2016

Brazilian

Antiterrorism

Law

is

primarily

a

result

of

international

pressure

coming

from

a

historically

influential

partner:

the

United

States.

Similarly,

the

process

of

approving

the

law

can

be

seen

as

part

of

a

project

for

Brazil’s

international

integration,

aiming

to

strengthen

economic

ties

with

developed

countries

and

align

the

country

with

global

norms

of

good

governance.

Ultimately,

it

could

also

be

a

strategically

convenient

instrument

for

the

criminalization

of

social

practices

typical

of

civil

resistance

groups

in Brazilian society.

© 2023-2024 Oriental Institute, The Czech Academy of

Sciences, Kevin L. Schwartz, and Ameem Lutfi

Written by

If you are interested in contributing an article for the

project, please send a short summary of the proposed

topic (no more than 200 words) and brief bio to

submissions@911legacies.com. For all other

matters, please contact inquiry@911legacies.com.

CONTACT