© 2023-2024 Oriental Institute, The Czech Academy of Sciences, Kevin L. Schwartz, and Ameem Lutfi

"The spirits that I summoned

I now cannot rid myself of again."

- Goethe's "Der Zauberlehrling," 1797

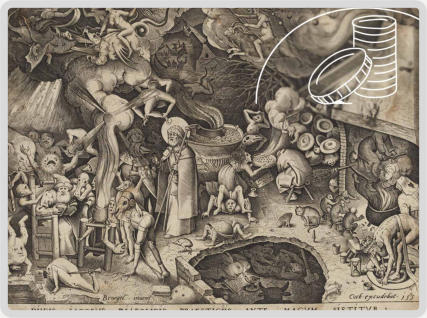

Few

images

better

reflect

America’s

response

to

the

attacks

of

9/11

as

well

as

Goethe’s

The

Sorcerer’s

Apprentice.

Charged

with

mopping

the

floor,

and

eager

to

diminish

the

pains

of

his

own

labor,

the

title

character

conjures

a

solution

in

the

form

of

a

magical

broom

that

makes

the

original

task

a

much

bigger

problem.

Almost

immediately

after

9/11,

the

United

States

began

to

“internationalize”

the

War

on

Terror,

mobilizing

a

collective

effort

among

nations

to

counter

global

terrorism

and

exporting

its

brand

of

solution

far

and

wide.

Among

the

most

problematic,

and

the

most

difficult

to

counteract,

was

the rapid proliferation and growth of international security assistance and cooperation programs, which, like the sorcerer’s magical mop, has created more problems than it has solved.

Since

9/11,

the

American

budget

for

providing

support

to

foreign

security

partners

has

nearly

doubled

—

twice

—

since

2002

(from

$5

billion

in

2001

to

$10

in

2003

and

then

to

nearly

$20

billion

in

2021).

The

number

of

countries

receiving

some

form

of

U.S.

security

assistance

or

support

to

contend

with

internal

security

problems

has

proliferated

to

the

point

that

many

more

countries

receive

assistance

than

do

not.

Unlike

some

of

the

more

infamous

programs

and

activities

(think

drone

strikes,

renditions,

and

torture),

security

assistance

does

little

to

stimulate

popular

or

political

resistance.

Cloaked

in

the

benign

language

of

“international

cooperation”

and

“local

ownership,”

and

entrenched

within

a

massive

bureaucracy

of

programs,

which

includes

a

sprawling

network

of

government

offices

and

contractors,

security

assistance

has

a

strong,

bipartisan

basis

of

support.

And

while

intense

scrutiny

has

—

rightfully

—

followed

the

use

of

more

direct

forms

of

counterterrorism,

security

assistance

has

spread

its

blight

in

other,

less

obvious,

ways

that

we

would

be

well

served

not

to

forget

if

we

wish

to

truly

move

past

America’s

endless

wars.

First,

American

counterterrorism

assistance

to

autocratic

regimes

has

grown

over

the

same

period

that

the

leaders

of

those

regimes

have

increasingly

cracked

down

on

civil

society

and

human

rights

defenders.

Under

the

new

legitimacy

bestowed

by

a

spirit

of

collective

action

to

counter

al-Qaeda,

and

a

new

language

that

could

be

used

to

obscure

intent,

140

governments

around

the

world

passed

counterterrorism

legislation

between

2001

and

2018.

Much

of

it

was

intended

to

stifle

political

dissent

and

restrict

the

conduct

of

human

rights

groups,

suppressing

the

one

meaningful

form

of

oversight

of

security

institutions

globally.

Rather

than

support

civil

society

in

the

face

of

restrictions

to

enhance

the

legitimacy

of

accountable

democracy,

the

United

States

shored

up

security

support

to

countries

like

Azerbaijan,

Cameroon,

Egypt,

and

the

Philippines

where

corrupt

,

rent-seeking

elites

in

government

have

long

used

security institutions and state-sponsored violence to maintain control.

Second,

analysts

and

academics

—

not

to

mention

practitioners

—

had

long

ago

identified

the

problem

that,

like

any

form

of

aid

,

many

if

not

most

forms

of

security

assistance

will

always

fail

to

achieve

the

objective

of

enhancing

partner

capacity

(or

improving

bilateral

cooperation

toward

shared

goals)

in

the

absence

of

certain

prerequisite

conditions.

But

as

a

political

strategy

for

reducing

the

cost

in

American

lives

by

removing

the

need

for

“boots

on

the

ground,”

America’s

political

leaders

doubled

down

on

building

partner

capacity

through

security

assistance

in

many

places,

like

Iraq,

where

they

simply

needed

it

to

work

,

swearing

to

outcomes

that

were

simply

not

possible

to

achieve

.

Not

only

did

the

overstatement

of

effectiveness

lead

to

massive

amounts

of

waste

and

corruption,

it

also

introduced

significant

moral

hazard

in

places

like

Mali

and

Afghanistan

,

where

the

local

public,

told

to

trust

in

the

magical

effects

of

security

assistance,

have

too

often

paid

the

price

for

American

perfidy

with

their

lives

as

local

security

forces

gave

way

to

the

so-

called

Islamic

State

or

the

Taliban.

Meanwhile,

in

other

places,

like

Nigeria,

where

the

West

made

an

early

bet

on

security

assistance

and

cooperation

—

rather

than

on

good

governance

and

human rights — the challenge to national government from armed groups has only metastasized (to use President Biden’s

own language

) and grown.

The

expansion

of

the

security

assistance

bureaucracy

from

the

War

on

Terror

will

do

as

all

bureaucracies

do:

it

will

shape-shift

and

find

a

new

cause

in

this

new

era

.

With

overwhelming

bipartisan

support,

the

Senate

in

June

2021

proposed

adding

an

additional

$645

million

to

the

foreign

military

financing

account

with

the

intent

of

supporting

local

partners

in

the

Asia

Pacific

region

as

a

means

of

competing

with

China.

Meanwhile,

secretive

counterterrorism,

security

assistance,

and

irregular

warfare

programs

continue

to

expand.

The

“

127e”

and

1202

programs

,

for

example,

both

received

extensions

and

increases

of

$5

million

in

funding

in

the

last

Defense

bill

,

along

with

a

vague

and

troubling

new

authority

to

expend

funds

“for

clandestine

activities

that

support operational preparation of the environment.”

And

so

even

as

the

United

States

ends

the

War

on

Terror

in

some

ways,

its

poisonous

tendrils

will

continue

to

spread

and

grow

in

others.

Once

summoned,

magical

solutions

from

Washington’s

spell book can be difficult to put back.

If you are interested in contributing an article for

the project, please send a short summary of the

proposed topic (no more than 200 words) and brief

bio to submissions@911legacies.com. For all

other matters, please contact

inquiry@911legacies.com.

CONTACT

"The spirits that I summoned

I now cannot rid myself of again."

- Goethe's "Der Zauberlehrling," 1797

Few

images

better

reflect

America’s

response

to

the

attacks

of

9/11

as

well

as

Goethe’s

The

Sorcerer’s

Apprentice.

Charged

with

mopping

the

floor,

and

eager

to

diminish

the

pains

of

his

own

labor,

the

title

character

conjures

a

solution

in

the

form

of

a

magical

broom

that

makes

the

original

task

a

much

bigger

problem.

Almost

immediately

after

9/11,

the

United

States

began

to

“internationalize”

the

War

on

Terror,

mobilizing

a

collective

effort

among

nations

to

counter

global

terrorism

and

exporting

its

brand

of

solution

far

and

wide.

Among

the

most

problematic,

and

the

most

difficult

to

counteract,

was

the

rapid

proliferation

and

growth

of

international

security

assistance

and

cooperation

programs,

which,

like

the

sorcerer’s

magical

mop,

has

created

more

problems than it has solved.

Since

9/11,

the

American

budget

for

providing

support

to

foreign

security

partners

has

nearly

doubled

—

twice

—

since

2002

(from

$5

billion

in

2001

to

$10

in

2003

and

then

to

nearly

$20

billion

in

2021).

The

number

of

countries

receiving

some

form

of

U.S.

security

assistance

or

support

to

contend

with

internal

security

problems

has

proliferated

to

the

point

that

many

more

countries

receive

assistance

than

do

not.

Unlike

some

of

the

more

infamous

programs

and

activities

(think

drone

strikes,

renditions,

and

torture),

security

assistance

does

little

to

stimulate

popular

or

political

resistance.

Cloaked

in

the

benign

language

of

“international

cooperation”

and

“local

ownership,”

and

entrenched

within

a

massive

bureaucracy

of

programs,

which

includes

a

sprawling

network

of

government

offices

and

contractors,

security

assistance

has

a

strong,

bipartisan

basis

of

support.

And

while

intense

scrutiny

has

—

rightfully

—

followed

the

use

of

more

direct

forms

of

counterterrorism,

security

assistance

has

spread

its

blight

in

other,

less

obvious,

ways

that

we

would

be

well

served

not

to

forget

if

we

wish

to

truly

move

past

America’s

endless wars.

First,

American

counterterrorism

assistance

to

autocratic

regimes

has

grown

over

the

same

period

that

the

leaders

of

those

regimes

have

increasingly

cracked

down

on

civil

society

and

human

rights

defenders.

Under

the

new

legitimacy

bestowed

by

a

spirit

of

collective

action

to

counter

al-Qaeda,

and

a

new

language

that

could

be

used

to

obscure

intent,

140

governments

around

the

world

passed

counterterrorism

legislation

between

2001

and

2018.

Much

of

it

was

intended

to

stifle

political

dissent

and

restrict

the

conduct

of

human

rights

groups,

suppressing

the

one

meaningful

form

of

oversight

of

security

institutions

globally.

Rather

than

support

civil

society

in

the

face

of

restrictions

to

enhance

the

legitimacy

of

accountable

democracy,

the

United

States

shored

up

security

support

to

countries

like

Azerbaijan,

Cameroon,

Egypt,

and

the

Philippines

where

corrupt

,

rent-seeking

elites

in

government

have

long

used

security

institutions

and

state-

sponsored violence to maintain control.

Second,

analysts

and

academics

—

not

to

mention

practitioners

—

had

long

ago

identified

the

problem

that,

like

any

form

of

aid

,

many

if

not

most

forms

of

security

assistance

will

always

fail

to

achieve

the

objective

of

enhancing

partner

capacity

(or

improving

bilateral

cooperation

toward

shared

goals)

in

the

absence

of

certain

prerequisite

conditions.

But

as

a

political

strategy

for

reducing

the

cost

in

American

lives

by

removing

the

need

for

“boots

on

the

ground,”

America’s

political

leaders

doubled

down

on

building

partner

capacity

through

security

assistance

in

many

places,

like

Iraq,

where

they

simply

needed

it

to

work

,

swearing

to

outcomes

that

were

simply

not

possible

to

achieve

.

Not

only

did

the

overstatement

of

effectiveness

lead

to

massive

amounts

of

waste

and

corruption,

it

also

introduced

significant

moral

hazard

in

places

like

Mali

and

Afghanistan

,

where

the

local

public,

told

to

trust

in

the

magical

effects

of

security

assistance,

have

too

often

paid

the

price

for

American

perfidy

with

their

lives

as

local

security

forces

gave

way

to

the

so-called

Islamic

State

or

the

Taliban.

Meanwhile,

in

other

places,

like

Nigeria,

where

the

West

made

an

early

bet

on

security

assistance

and

cooperation

—

rather

than

on

good

governance

and

human

rights

—

the

challenge

to

national

government

from

armed

groups

has

only

metastasized

(to

use

President

Biden’s

own language

) and grown.

The

expansion

of

the

security

assistance

bureaucracy

from

the

War

on

Terror

will

do

as

all

bureaucracies

do:

it

will

shape-shift

and

find

a

new

cause

in

this

new

era

.

With

overwhelming

bipartisan

support,

the

Senate

in

June

2021

proposed

adding

an

additional

$645

million

to

the

foreign

military

financing

account

with

the

intent

of

supporting

local

partners

in

the

Asia

Pacific

region

as

a

means

of

competing

with

China.

Meanwhile,

secretive

counterterrorism,

security

assistance,

and

irregular

warfare

programs

continue

to

expand.

The

“

127e”

and

1202

programs

,

for

example,

both

received

extensions

and

increases

of

$5

million

in

funding

in

the

last

Defense

bill

,

along

with

a

vague

and

troubling

new

authority

to

expend

funds

“for

clandestine

activities

that

support

operational

preparation

of

the environment.”

And

so

even

as

the

United

States

ends

the

War

on

Terror

in

some

ways,

its

poisonous

tendrils

will

continue

to

spread

and

grow

in

others.

Once

summoned,

magical

solutions

from

Washington’s

spell book can be difficult to put back.

© 2023-2024 Oriental Institute, The Czech Academy of

Sciences, Kevin L. Schwartz, and Ameem Lutfi

Written by

If you are interested in contributing an article for the

project, please send a short summary of the proposed

topic (no more than 200 words) and brief bio to

submissions@911legacies.com. For all other

matters, please contact inquiry@911legacies.com.

CONTACT